- Research

- Open access

- Published:

The role of family doctors in developing primary care systems in Asia: a systematic review of qualitative research conducted in middle-income countries 2010–2020

BMC Primary Care volume 25, Article number: 346 (2024)

Abstract

Background

The Asia Pacific Region’s middle-income countries (MICs) face unique challenges in the ongoing development of primary care (PC) systems. This development is complicated by systemic factors, including rapid policy changes and the introduction of private healthcare services, as well as the mounting challenges associated with ageing populations and increasing rates of chronic diseases. Despite the widespread acknowledgement of the importance of family doctors in the development of PC services, relatively little is known about how these roles have developed in Asian MICs. To address this gap, this systematic review presents a synthesis of recent research focused on the role of family doctors within the PC systems of MICs in the Asia Pacific Region.

Methods

We searched six electronic databases (CINAHL Complete, Embase, PsycINFO, PubMed, Web of Science, and Index Medicus for the South-East Asia Region and Western Pacific) for peer-reviewed qualitative literature published between January 2010 and December 2020. The quality of the studies was evaluated using the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme tool. Eighteen articles were included in the analysis. Findings from these articles were extracted and synthesised using qualitative thematic synthesis. We used the Rainbow Framework to analyse the interconnections within health systems at the macro, meso and micro levels.

Results

Our analysis of the included articles showed that family doctors play a crucial role in bridging the gap between hospitals and communities. They are essential in adopting holistic approaches to health and wellbeing and are in a unique position to try and address social, psychological, and biological aspects of health. Our findings also highlight the influence of policy changes at the macro level on the role and responsibilities of family doctors at the meso (organisational) and micro (interpersonal) levels.

Conclusions

Limited research has explored the role of family doctors in the ongoing development of primary care systems in MICs in the Asia Pacific Region. The findings of this review have significant implications for policymakers and healthcare administrators involved in ongoing improvements to and strengthening of PC systems. Areas of particular concern relate to policy linked with training and workforce development, insurance systems and public awareness of what primary care services are.

Background

The principles of primary health care (PHC) have been an international priority since the Alma-Ata Declaration in 1978 [1]. High-income countries such as Australia and the UK have made significant improvements in working towards the objectives and ways of thinking about accessible health and care at both individual and population levels [2] through the provision of primary care (PC) services including those led by family doctors [3]. Progress in low- and middle-income countries (LIC and MICs) Footnote 1 has been more limited and associated weaknesses were evident in the difficulties health systems faced during the COVID-19 pandemic [4]. Despite inconsistent progress in the development of PC services, the principles of PHC remain the most promising for addressing global health challenges including those associated with ageing populations and increases in chronic diseases [5, 6]. The World Health Organization (WHO) has restated its support of principles of prevention, social justice, equity, solidarity and participation in healthcare in reports including “Primary health care now more than ever” [7] as well as the more recent Astana Declaration [5]. LIC and MICs governments have continued to state their commitment to strengthening the connections between health and social care systems that facilitate the transition from reliance on hospital-level care to services delivered to individuals through community-based services [8].

Research in countries with highly developed healthcare systems has consistently highlighted the key role of family doctors (also referred to as General Practitioners; this review uses ‘family doctor’ throughout for consistency) [9] in the provision of community-based PC services. Family doctors serve as gatekeepers into health systems [10] and play a crucial role in coordinating and responding to the needs of local communities [11]. In well-functioning systems, high levels of public awareness allow family doctors to actively cultivate positive and ongoing relationships with service users [2]. These relationships have various effects on system development including promoting access to services, continuity of care, and the effective management of physical and mental health [11]. This holistic approach can contribute to the potential alleviation of poor health outcomes associated with poverty and structural inequality [12, 13].

From a global perspective, MICs face particular challenges in the development of PC systems [14]. These locations may now be caught in the ‘double-bind’ of contending with high rates of infectious diseases while also being confronted with rapid growth in chronic diseases [14]. Additionally, individual access to services may be curtailed by limited or uneven public health insurance systems [15]. To date, most reviews of PC development have focused on variables of income status [14, 16] with little attention directed towards regional sociocultural factors that may shape responses to the development of PC.

In this systematic review, we focus on what is known about family doctors’ perceptions and experiences of their role in PC systems in MICs located in the Asia Pacific RegionFootnote 2. This region is densely populated, socially and culturally diverse and characterised by uneven economic development [16, 17]. Additionally, services within the region have shown a slow transition from hospital to community-based services despite the increasing pressures associated with rapidly ageing populations [18]. Recent research within the region has primarily focused on the macro context of policy or programme innovations in single locations [19] with limited attention directed towards exploring broader social and systemic factors that promote or limit PC development [20]. In response to this lacuna, our review presents a synthesis of recently published empirical qualitative research articles based on research conducted in MICs in the Asia Pacific Region. Research published between 2010 and 2020 was selected for inclusion as this period reflects a key time of regional policy development linked with relevant WHO initiatives and before the severe disruption to PC services caused by the COVID-19 pandemic [21]. To facilitate an in-depth and cross-cutting analysis, the Rainbow Framework [22] was used to examine the interconnections within health systems at the macro (societal and policy context), meso (organisational and managerial factors), and micro (patient and provider interactions) levels. The findings of this review will inform policymakers and healthcare administrators engaged in the development of PC systems including the strengthening of initiatives associated with public awareness, education and workforce development.

Methods

This systematic review was registered prospectively with PROSPERO (CRD42023439032) and this entry has been updated periodically. Findings are reported in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA 2020) guidelines [23].

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

To be eligible for inclusion, articles needed to report on original, empirical, and qualitative research published in international peer-reviewed journals between January 2010 and December 2020. Data needed to be collected from locations within the Asia Pacific Region with research questions primarily focused on family doctors’ perceptions of their role in the development of PC services. These inclusion criteria are summarised in Table 1. Articles were excluded if research questions and data collection focused on hospital settings (secondary/tertiary care), non-doctor health workers in PC settings, medical students or trainees, perspectives of patients and/or policymakers, or evaluations of training programs for family doctors.

Searches

Six electronic databases (CINAHL Complete, Embase, PsycINFO, PubMed, Web of Science, and Index Medicus for the South-East Asia Region and Western Pacific) were searched manually for relevant peer-reviewed literature published between January 2010 and December 2020. Print and online sources were included. No language restrictions were applied to the searches. Geographical locations were selected based on the World Bank’s country income classifications and the WHO map of regionsFootnote 3. Refer to Appendix 1 for the complete search strategy and associated rationale.

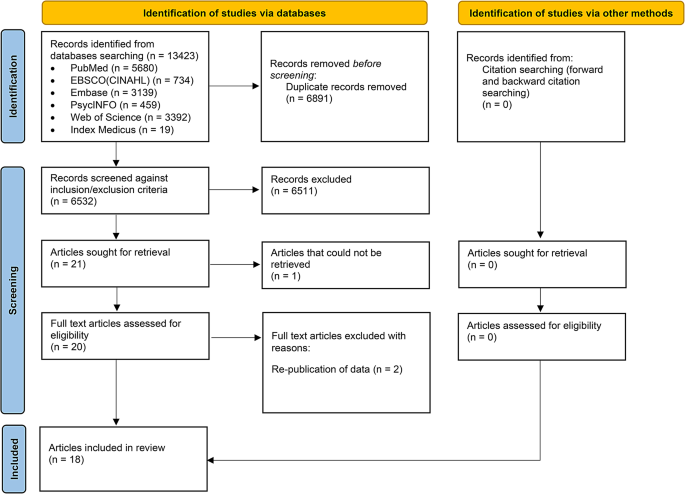

Original searches for studies published between 2010 and 2020 were run in June and August 2023. At this time, 998 articles were found and then after removal of duplications and screening, 12 articles were deemed eligible. After further input from an expert librarian and reviewers, the protocol was revised and searches were re-run in June and July 2024 using expanded search terms with the same publication timeframes (2010–2020). All other inclusion and eligibility criteria were unchanged. The re-run searches returned 13,423 articles. Following the removal of duplicates, 6,532 articles were identified for screening against the inclusion criteria by the first author (BL), and 20 full-text articles were assessed for eligibility. In total, 18 articles were identified through the search process. Both authors agreed on inclusions after evaluating each article’s eligibility against inclusion and exclusion criteria. Citation searching (forward and backward citation searching) was then conducted and no additional articles were identified.

Study quality appraisal

Methods for the appraisal of study quality in systematic reviews are contentious [25, 26]. We followed the practice of Damarell et al. [27] and appraised the ethical and methodological choices described in each study included in the review [27]. The full texts of the eighteen articles identified were appraised by both authors using the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) checklist [28]. In line with Noyes et al. [29], both authors engaged in discussions about the included studies, evaluating each paper’s rigour, methodological limitations and potential contributions to local knowledge and services. Authors agreed before the final appraisal that the only grounds for exclusion were inadequate or absent reporting of ethical approval. All included studies reported appropriate ethical approval and thus no articles were excluded at this stage. The results of the CASP and discussion of the potential contributions of individual articles are provided in Table 2.

Data extraction strategy

Study information from the eighteen included articles was extracted by both authors. Extracted details included author/s and year of publication, location of data collection, research objectives, data collection method, participants, and main findings (Table 3).

Data synthesis and presentation

Qualitative thematic synthesis [47] was used to synthesize the findings of the included studies. Both authors independently and inductively coded the results and/or findings from all studies. This process began with line-by-line coding. Codes were then grouped into descriptive themes. Finally, analytic themes, identified by consolidating descriptive themes, were developed. Any discrepancies were addressed through ongoing discussion between the authors.

Results

This review included eighteen empirical research articles that focused on family doctors’ perceptions and experiences of their role in PC development. Figure 1 shows the PRISMA 2020 flowchart of the searches that were re-run in June and July 2024. Despite all MICs in the Asia Pacific Region being included in the database searches, articles that were deemed eligible for inclusion in the review were based on data collected in a limited number of locations specifically Mainland China (hereafter referred to as China), Hong Kong Special Administrative Region (hereafter referred to as Hong Kong), India, Indonesia, and Malaysia. The significance of the lack of research available from other locations in the region is discussed later in this article. The five locations represented in the articles included in the review have all undergone rapid policy-led PC developments in recent years and this may have contributed to a growth in related research. For example, China’s PC system has been significantly reformed and networks of community centres and clinics have been established [43]. Hong Kong has a more established PC system, comprised of both public and private sectors. This system offers a blend of subsidised public clinics and private practices to manage a wide range of health issues [48]. Recent policy initiatives in India, Indonesia and Malaysia have focused on the development of policy and education initiatives to extend public and private PC services with family doctors increasingly positioned as key stakeholders [30, 34, 37].

Qualitative thematic synthesis identified key factors that influenced family doctors’ involvement in the development of local PC programs. In keeping with the Rainbow Framework [22], these factors were analysed across macro, meso and micro dimensions of PC systems. Although these dimensions of health systems are interconnected and porous, using this framework for analysis and discussion highlights some of the structural and systemic challenges in the region that may influence the ongoing development and strengthening of local PC services.

Macro: Health system policy and capacity for PC development

Research included in the review highlighted the influence of government policy on both the capacity of PC systems as well as the ability of family doctors to actively promote the development of the sector. Key factors were associated with (1) overarching health system policies including those related to health insurance and regulation of the sector, and (2) limited systemic refocusing/pivoting towards PC service delivery.

Overarching health system policies

Most articles acknowledged the impact of the overarching government policies that shaped the macro system in which PC was located [13, 34, 36, 43,44,45,46]. A key issue identified in China, India, Indonesia and Malaysia related to the absence of comprehensive health insurance that restricted access to and development of PC. This lack of comprehensive insurance limited patients’ ability to access PC and, at times, led to reported increases in self-medication [34], delays in seeking necessary medical help [13], and limited access to mental health treatment [43]. A lack of policy initiatives that aimed to develop post-qualification specialist training for family doctors on key topics including mental health, men’s health and women’s sexual dysfunction were also noted as a factor that restricted the development of PC systems [36, 43, 44, 46].

Limited systemic refocusing/pivoting towards PC

Research included in this review reflected broader concerns expressed by family doctors across locations about the limited refocusing or pivoting towards the development of a PC-oriented health system. Research participants claimed that this was evident in inadequate government regulation and oversight of PC services. The lack of regulation of PC systems in India was linked to limited control over the distribution of medicine, leading to patients obtaining antibiotics from unqualified prescribers or dispensers [34]. Additionally, the absence of monitoring systems in private PC services provided by midwives and nurses in Indonesia was reported to result in the provision of services beyond their professional or legal competencies [13].

A lack of regulation of professional training – including postgraduate qualifications and continuous professional development (CPD) – was also identified as restricting the development of the role of family doctors within PC systems [30, 41, 45, 46]. Research participants in China noted that although there were national General Practitioners (GPs) training programs for community-based family doctors, the content was not differentiated to reflect the diverse needs of doctors working in community (rather than hospital) locations or settings [45]. In research from India, it was reported that formal training in family medicine for family doctors was only recently introduced to the medical system through government-led policy [40].

Across the included studies, family doctors reported facing constraints within the health system that limited broadening their scope of practice to include mental health and social issues related to health and well-being [37, 38, 43, 46]. Despite recognising their role as the first point of contact for patients, family doctors in China, Indonesia and Malaysia reported difficulties in working to address and manage general health issues due to the absence of government policies and guidelines that specifically authorised the inclusion of these areas in the remit of their work [37, 38, 43]. This was evident in the low priority given to mental health in China, and the consequent underdiagnosis and limited access to appropriate treatments [43, 46]. In Malaysia, doctors expressed an awareness of social issues such as elder abuse and neglect but did not perceive such issues as priorities during clinical consultations due to a lack of guidelines or reporting systems for these areas of care [37]. Similarly, in Indonesia, family doctors found it difficult to engage in the management of suspected violence against women as there were no standard operational procedures to direct their intervention [38].

Limited public awareness of the purpose of PC and its interaction with social and cultural norms was also widely reported to impact the work of family doctors [35,36,37, 40, 41, 43,44,45,46]. The lack of public awareness of the role of preventative health care [44], the stigma surrounding mental health [43] and social taboos associated with issues including elder abuse [37], adolescent abortion [35], and female sexual dysfunction [36] also restricted the capacity and motivation of family doctors to engage in delivering these services. Doctors encountered sensitivity, resistance and wariness when broaching these topics due to social and cultural taboos and confusion about the role of the family doctor in the management of these issues [37]. This public misunderstanding of family medicine at multiple levels of the health care system in India was linked by research participants with a common misperception that low-cost PC was low-quality care [40].

Meso level challenges

The research included in the review highlighted how changes in the macro systems had knock-on effects at the meso (organisational) level in relation to (1) service delivery, (2) rural and urban disparities, and (3) challenges in specialist education and continuing professional development for family doctors.

Limitations in service delivery

Changes in macro systems had significant effects on the level of clinical service delivery. In addition to the low priority given to mental health and other issues, the lack of guidelines, policies, support systems and healthcare resources meant that family doctors often did not know how to deliver services in line with PC objectives [34, 43, 46]. For example, doctors in community healthcare centres in Shenzhen, China, identified a lack of personnel, treatment options, and consultation rooms as restricting their capacity to incorporate mental health care services into local PC service delivery [43]. Additionally, funding for medical treatment and the development of specialist facilities often remained with the hospitals rather than being devolved out to PC settings [43, 46].

Service delivery was also limited by low levels of public health literacy and awareness of PC [43, 46]. This was, in turn, linked with issues such as self-medication and antibiotics overuse [34], low treatment adherence [34], and limited health literacy in relation to mental health and preventative interventions [43, 44]. Research participants discussed their ongoing work in advocating for urgent government policy change in order to promote public awareness of PC and how citizens could access services and resources [43, 34].

Exacerbation of rural and urban disparities

Disparities in the distribution of resources between rural and urban areas and the impact on the division between primary and secondary/tertiary care settings presented various challenges to the development of the role of family doctors in PC. Research conducted in rural areas in Malaysia and Indonesia identified challenges including staff shortages, inadequate medicine supplies, a lack of essential equipment and facilities, and limitations in professional training systems [31, 33]. Disparities in income and career development were identified by research participants in Indonesia as making local recruitment more difficult [33].

Malaysian research also described some family doctors in rural areas as devising information innovations or ‘work arounds’ to address local gaps in PC services [31]. For example, some family doctors implemented a ‘buddy system’ to seek assistance from specialists [31].

Challenges in specialist education and continuing professional development

Similar issues in relation to ongoing education were reported by family doctors in urban locations [39, 41, 43, 46]. Family doctors in Shanghai and Shenzhen, China, expressed a desire and commitment to increasing their skills and knowledge in relation to mental health care in PC but reported that they lacked access to training about how to diagnose mental health issues in PC settings [43, 46]. Some doctors in Shenzhen reported that in the absence of mental health guidelines for PC settings, they extended their own clinical practices through self-directed learning which included developing screening instruments to aid in the diagnosis of mental health conditions [43]. In Hong Kong, due to limited learning opportunities provided by formal organisations, family doctors often devised their own CPD activities in small professional groups [39]. These informal groups allowed them to establish stable peer support systems, discuss clinical practice and update their clinic knowledge by inviting specialists to give talks to the community members [39]. Likewise, some private family doctors in Malaysia formed informal peer support groups to exchange information and CPD resources [41].

Micro level challenges

Research included in this review also highlighted the limitations family doctors experienced in their everyday interactions with PC patients. These limitations at the micro level were influenced by the broader factors that shaped the meso and macro levels.

Time constraints

Family doctors highlighted the negative impact of short consultation times, which severely reduced their ability to engage in what they considered to be comprehensive PC [13, 30,31,32, 34, 35, 37,38,39, 42, 43, 45]. Doctors in Malaysia reported that the high patient-to-doctor ratio led to an overwhelming workload and extremely short consultation times [31, 32]. Doctors across the studies reported that due to heavy workloads they did not have time to inquire about patients’ family history [32], educate patients about the proper use of antibiotics [34], identify risk factors and utilise depression screening tools [43], follow-up concerns about elder abuse [37] or domestic violence [38], investigate cases of adolescent pregnancy [35], seek evidence-based answers [31], or attend CPD programs and activities [30, 41, 45].

Challenges to professional identity as family doctors

Family doctors reported that a lack of awareness of their specialised role within the broader healthcare environment limited their influence within the PC system and, thus, restricted the development of impactful relationships with PC patients [35, 37, 38, 40, 42, 43, 46]. Doctors linked this lack of professional identity with feelings of disillusionment and low levels of acknowledgement of the value of their role by the broader society [40]. Although some doctors in the research studies acknowledged their potential to be involved in the management of mental health disorders [43] or elder abuse [37], they still identified their key function as being to address the clinical presentation of patients rather than dealing with broader social issues that may impact health and wellbeing [37]. It is of significance that a number of studies highlighted participants lack of confidence in identifying and managing mental illnesses and broader health issues [37, 38, 43, 46]. This lack of confidence was attributed to several factors, including limited training and experience, poor learning support structures, inadequate government guidelines, and insufficient support systems [37, 43, 46]. In some cases, in China, even when training schemes were available, the excessive clinical workload and lack of staffing made it difficult for doctors to attend training programs [43, 46]. Doctors viewed these barriers to attending training as problematic as they greatly valued CPD and considered it to be an important way of staying up-to-date with the latest medical knowledge and best practices [39, 41, 45].

Discussion

This systematic review has explored what is currently known about the role of family doctors in PC systems in MICs in the Asia Pacific Region. The family doctor is widely acknowledged as being a key point of connection between hospitals and communities and also facilitates holistic approaches to health and wellbeing as they connect across social, psychological and biological domains.

The findings of this review highlight the interconnected nature of PC systems and the significant impact of policy changes at the macro level on the role and work of family doctors at both the meso (organisational) and micro (interpersonal) levels. Research included in the review has shown that overarching policy changes often have effects that essentially limit the development of the role of the family doctor and thus stall or slow down broader improvements in PC. Limited public insurance coverage, low levels of health literacy and awareness of what PC is limit opportunities for engagement of family doctors with PC patients. Additionally, restricted education and professional development opportunities and narrow views of the role of family doctors also hinder development.

The findings of this review highlight the need for all parties involved in developing PC to recognize the interconnected nature of the macro, micro and meso levels of health care systems. For example, policy innovations may increase the number of people who are eligible to access PC services but if this is not done in tandem with changes at the levels of workforce development, professional education, local service development and public awareness raising then ongoing PC improvement will be limited.

Limitations

There are two limitations associated with this review that need to be acknowledged. Firstly, initial and potentially restrictive search terms used in 2023 were expanded for the re-running of the searches in June and July 2024 (publication time-frames and all other inclusion and eligibility criteria were unchanged). Despite this modification, searches returned literature from only a limited number of MICs within the Asian Pacific Region (China, Hong Kong, India, Indonesia, and Malaysia). This lack of representativeness limits the potential to draw inferences from the experiences of family doctors in other MICs in the region. To address this paucity of published, peer-reviewed literature from some of the MICs within the region, future research on this topic could usefully include grey literature such as government reports, policy documents and information from professional and educational institutions. The second limitation of this review relates to the potential for findings to be incorporated into policy and practice guidelines. Although the findings will be of interest to a range of PC stakeholders, it is increasingly acknowledged that confidence in the representativeness of findings of qualitative systematic reviews and therefore their potential to be incorporated into policy and practice are enhanced by the use of tools such as GRADE-CERQual [49]. It is recommended that future research on this topic makes use of such a tool in order to optimise the uptake of findings by policy makers and practitioners across locations.

Conclusion

The development of well-functioning PC systems in MICs in the Asia Pacific Region remains challenging. The findings of this systematic review highlight that to achieve progress in PC development, family doctors need to be actively engaged across macro, meso and micro levels of service change. Additional research is needed to explore strategies that enable family doctors to play a more effective role in the PC system during the health transition of MICs in the Asia Pacific Region.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Notes

World Bank country classifications by income level: https://blogs.worldbank.org/en/opendata/new-world-bank-country-classifications-income-level-2022-2023.

World Health Organization: https://www.who.int/about/structure;

World Health Organization. Regional Office for South-East Asia. (2008). Health in Asia and the Pacific. WHO Regional Office for South-East Asia. https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/205227.

Abbreviations

- CASP:

-

Critical Appraisal Skills Programme

- CPD:

-

Continuous professional development

- GP:

-

General Practitioner

- MICs:

-

Middle-income countries

- PC:

-

Primary care

- PHC:

-

Primary healthcare

- PRISMA:

-

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

References

Hone T, Macinko J, Millett C. Revisiting Alma-Ata: what is the role of primary health care in achieving the Sustainable Development Goals? Lancet. 2018;392(10156):1461–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31829-4.

Papanicolas I, Mossialos E, Gundersen A, Woskie L, Jha AK. Performance of UK national health service compared with other high income countries: observational study. BMJ. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.l6326.

Gauld R, Blank R, Burgers J, Cohen AB, Dobrow M, Ikegami N, et al. The World Health Report 2008 - primary healthcare: how wide is the gap between its agenda and implementation in 12 high-income health systems? Healthc Policy. 2012;7(3):38–58.

Peiris D, Sharma M, Praveen D, Bitton A, Bresick G, Coffman M, et al. Strengthening primary health care in the COVID-19 era: a review of best practices to inform health system responses in low- and middle-income countries. WHO South East Asia J Public Health. 2021;10:6–25.

World Health Organization. Astana Declaration on primary health care: From Alma-Ata towards Universal Health Coverage and the Sustainable Development Goals. 2018. http://www.who.int/primary-health/conference-phc/declaration Accessed 24 Sep 2023.

Muldoon LK, Hogg WE, Levitt M. Primary care (PC) and primary Health Care (PHC). Can J Public Health. 2006;97:409–11. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03405354.

World Health Organization. The world health report 2008: primary health care now more than ever. 2008. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/43949 Accessed 24 Sep 2023.

Langlois EV, McKenzie A, Schneider H, Mecaskey JW. Measures to strengthen primary health-care systems in low- and middle-income countries. Bull World Health Organ. 2020;98(11):781–91.

Kidd M. The contribution of family medicine to improving health systems: a guidebook from the World Organization of Family doctors. CRC press; 2020.

Mulyanto J, Wibowo Y, Kringos DS. Exploring general practitioners’ perceptions about the primary care gatekeeper role in Indonesia. BMC Fam Pract. 2021;22(5):1–10. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12875-020-01365-w.

Clatney L, MacDonald H, Shah SM. Mental health care in the primary care setting: family physicians’ perspectives. Can Fam Physician. 2008;54(6):884–9.

Morgan K, Williamson E, Hester M, Jones S, Feder G. Asking men about domestic violence and abuse in a family medicine context: help seeking and views on the general practitioner role. Aggress Violent Behav. 2014;19(6):637–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2014.09.008.

Syah NA, Roberts C, Jones A, Trevena L, Kumar K. Perceptions of Indonesian general practitioners in maintaining standards of medical practice at a time of health reform. Fam Pract. 2015;32(5):584–90. https://doi.org/10.1093/fampra/cmv057.

Palagyi A, Dodd R, Jan S, Nambiar D, Joshi R, Tian M, et al. Organisation of primary health care in the Asia-Pacific region: developing a prioritised research agenda. BMJ Glob Health. 2019;4:e001467. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjgh-2019-001467.

Angell B, Dodd R, Palagyi A, Gadsden T, Abimbola S, Prinja S, et al. Primary health care financing interventions: a systematic review and stakeholder-driven research agenda for the Asia-Pacific region. BMJ Glob Health. 2019;4:e001481. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjgh-2019-001481.

Dodd R, Palagyi A, Jan S, Abdel-All M, Nambiar D, Madhira P, et al. Organisation of primary health care systems in low- and middle-income countries: review of evidence on what works and why in the Asia-Pacific region. BMJ Glob Health. 2019;4:e001487. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjgh-2019-001487.

The World Bank. (n.d.). New World Bank country classifications by income level: 2022–2023. https://blogs.worldbank.org/en/opendata/new-world-bank-country-classifications-income-level-2022-2023. Accessed 24 Sep 2023.

Chang L, Shenglan T. Integrated care for chronic diseases in Asia Pacific countries. New Delhi; 2021. https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/345181/9789290228912-eng.pdf?sequence=1 Accessed 24 Sep 2023.

Kassai R, van Weel C, Flegg K, Tong SF, Han TM, Noknoy S, et al. Priorities for primary health care policy implementation: recommendations from the combined experience of six countries in the Asia–Pacific. Aust J Prim Health. 2020;26(5):351–7. https://doi.org/10.1071/PY19194.

Goodyear-Smith F, Bazemore A, Coffman M, Fortier R, Howe A, Kidd M, et al. Primary care research priorities in low-and middle-income countries. Annals Family Med. 2019;17(1):31–5. https://doi.org/10.1370/afm.2329.

Rasanathan K, Evans TG. Primary health care, the declaration of Astana and COVID-19. Bull World Health Organ. 2020;98(11):801–8. https://doi.org/10.2471/BLT.20.252932.

Valentijn PP, Schepman SM, Opheij W, Bruijnzeels MA. Understanding integrated care: a comprehensive conceptual framework based on the integrative functions of primary care. Int J Integr Care. 2013;13:e010. https://doi.org/10.5334%2Fijic.886.

Page MJ, Moher D, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. PRISMA 2020 explanation and elaboration: updated guidance and exemplars for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372:n160.

World Health Organization. Regional office for South-East Asia. Health in Asia and the Pacific. WHO Regional Office for South-East Asia; 2008. https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/205227. Accessed 19 Jul 2024.

Carroll C, Booth A, Lloyd-Jones M. Should we exclude inadequately reported studies from qualitative systematic reviews? An evaluation of sensitivity analyses in two case study reviews. Qual Health Res. 2012;22(10):1425–34. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732312452937.

Sandelowski M. BJ. Handbook for synthesizing qualitative research. Springer Publishing Company; 2006.

Damarell RA, Morgan DD, Tieman JJ. General practitioner strategies for managing patients with multimorbidity: a systematic review and thematic synthesis of qualitative research. BMC Fam Pract. 2020;21:1–23. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12875-020-01197-8.

Critical Appraisal Skills Programme. CASP Qualitative Checklist. 2018. https://casp-uk.net/checklists/casp-qualitative-studies-checklist-fillable.pdf Accessed 17 Jul 2024.

Noyes J, Booth A, Moore G, Flemming K, Tuncalp O, Shakibazadeh E. Synthesising quantitative and qualitative evidence to inform guidelines on complex interventions: clarifying the purposes, designs and outlining some methods. BMJ Glob Health. 2019;4:e000893. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjgh-2018-000893.

Ekawati FM, Claramita M, Istiono W, Kusnanto H, Sutomo AH. The Indonesian general practitioners’ perspectives on formal postgraduate training in primary care. Asia Pac Fam Med. 2018;17(1):10. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12930-018-0047-9.

Hisham R, Liew SM, Ng CJ. A comparison of evidence-based medicine practices between primary care physicians in rural and urban primary care settings in Malaysia: a qualitative study. BMJ Open. 2018;8(7):e018933. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2017-018933.

Hussein N, Malik TFA, Salim H, Samad A, Qureshi N, Ng CJ. Is family history still underutilised? Exploring the views and experiences of primary care doctors in Malaysia. J Community Genet. 2020;11:413–20. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12687-020-00476-2.

Handoyo NE, Prabandari YS, Rahayu GR. Identifying motivations and personality of rural doctors: a study in Nusa Tenggara Timur, Indonesia. Educ Health (Abingdon). 2018;31(3):174–7.

Kotwani A, Wattal C, Katewa S, Joshi PC, Holloway K. Factors influencing primary care physicians to prescribe antibiotics in Delhi India. Fam Pract. 2010;27(6):684–90. https://doi.org/10.1093/fampra/cmq059.

Malek KA, Abdul-Razak S, Abu Hassan H, Othman S. Managing adolescent pregnancy: the unique roles and challenges of private general practitioners in Malaysia. Malays Fam Physician. 2019;14(3):37–45. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32175039.

Muhamad R, Horey D, Liamputtong P, Low WY. Managing women with sexual dysfunction: difficulties experienced by Malaysian family physicians. Arch Sex Behav. 2019;48:949–60. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-018-1236-1.

Mohd Mydin FH, Othman S. Elder abuse and neglect intervention in the clinical setting: perceptions and barriers faced by primary care physicians in Malaysia. J Interpers Violence. 2020;35(23–24):6041–66. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260517726411.

Purwaningtyas NH, Wiwaha G, Setiawati EP, Arya IFD. The role of primary healthcare physicians in violence against women intervention program in Indonesia. BMC Fam Pract. 2019;20(1):168. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12875-019-1054-0.

Poon MK, Lam TP. Factors affecting the development and sustainability of communities of practice among primary care physicians in Hong Kong. J Contin Educ Health Prof. 2017;37(2):70–5. https://doi.org/10.1097/CEH.0000000000000153.

Rahman SMF, Vingilis E, Hameed S. Views of physicians on the establishment of a department of family medicine in South India: a qualitative study. J Family Med Prim Care. 2019;8:3214. https://doi.org/10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_551_19.

Samad NA, Md Zain A, Osman R, Lee PY, Ng CJ. Malaysian private general practitioners’ views and experiences on continuous professional development: a qualitative study. Malays Fam Physician. 2014;9:34–40.

Saw PS, Nissen L, Freeman C, Wong PS, Mak V. Exploring the role of pharmacists in private primary healthcare clinics in Malaysia: the views of general practitioners. J Pharm Pract Res. 2017;47(1):27–33. https://doi.org/10.1002/jppr.1195.

Searle K, Blashki G, Kakuma R, Yang H, Zhao Y, Minas H. Current needs for the improved management of depressive disorder in community healthcare centres, Shenzhen, China: a view from primary care medical leaders. Int J Ment Health Syst. 2019;13(1):1–18. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13033-019-0300-0.

Tong SF, Low WY, Ismail SB, Trevena L, Willcock S. Malaysian primary care doctors’ views on men’s health: an unresolved jigsaw puzzle. BMC Fam Pract. 2011;12:29. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2296-12-29.

Zhu E, Fors U, Smedberg Å. Exploring the needs and possibilities of physicians’ continuing professional development - an explorative qualitative study in a Chinese primary care context. PLoS ONE. 2018;13:e0202635. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0202635.

Zhang H, Yu D, Wang Z, Shi J, Qian J. What impedes general practitioners’ identification of mental disorders at outpatient departments? A qualitative study in Shanghai, China. Ann Glob Health. 2019;85:134. https://doi.org/10.5334/aogh.2628.

Thomas J, Harden A. Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2008;8(1):45. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-8-45.

Wong SY, Kung K, Griffiths SM, Carthy T, Wong MC, Lo SV, et al. Comparison of primary care experiences among adults in general outpatient clinics and private general practice clinics in Hong Kong. BMC Public Health. 2010;10:397. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-10-397.

Lewin S, Booth A, Glenton C, Munthe-Kaas H, Rashidian A, Wainwright M, et al. Applying GRADE-CERQual to qualitative evidence synthesis findings: introduction to the series. Implement Sci. 2018;13:2. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-017-0688-3.

Funding

This research is funded by a grant from the Hong Kong Polytechnic University to Margo Turnbull (corresponding author) [project number P0045897].

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MT was responsible for original conceptualisation and funding acquisition. BL and MT were responsible for data acquisition, analysis and writing of the manuscript. Both authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, B., Turnbull, M. The role of family doctors in developing primary care systems in Asia: a systematic review of qualitative research conducted in middle-income countries 2010–2020. BMC Prim. Care 25, 346 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12875-024-02585-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12875-024-02585-0